What keeps you running? About motivation at work.

Posted by encognize G.K. in Know thyself, Know your team on March 24, 2012

“The heart has its reasons which reason knows not of.”

– Blaise Pascal, French mathematician, physicist and theologian (1623-1662)

Abstract:

Every manager knows it: nothing extraordinary will happen in their teams without their members being clearly motivated. Reviewing the results of the recent researches in psychology and peeping at some of the classical theories that aim at defining what motivation is about will potentially help you clarify your own drivers as well as identify the inner motivations of each one of your team members. It will then be up to you, as a manager, to design your team objectives and to model behaviors that will keep everyone’s motivation as high as possible, setting the team for a long-lasting success through increased performance and commitment.

Concept:

Why talking about “motivation”?

Individual and collective performance is commonly described as a function of the 4 following variables:

- competencies, skills and knowledge of the team members

- organization’s quality (including among others: a common vision, inspiring leaders, a corporate culture, clear objectives…)

- ability for the staff to work as a team

- employee’s motivation

It is therefore key to understand what “motivation” is about in order to define strategies aimed at increasing the overall performance of your teams.

What is “motivation”?

In the past decades, abundant psychology researches on “motivation” and more specifically on “motivation at work” have led to a large number of theories. Below is a short presentation of 4 interesting theories.

- Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (1954):

Maslow’s model classifies human needs in 5 categories hierarchized from the most fundamental levels of needs to the most complex ones as follow: physiological needs (food, sleep…), safety needs (security of body, resources, health…), love and belonging (be accepted, loved, listened by the others, friendship, family…), esteem (self-esteem, confidence, achievement, respect by others…) and self-actualization (desire to become everything that one is capable of becoming).

According to Maslow, once one has satisfied one level of needs, starting from the most fundamental ones (bottom of the below pyramid), one may look at satisfying the following level.

Maslow acknowledges though that different level of motivation aimed at satisfying different level of needs may be going at once for a given individual, with the domination of a certain need; this has obviously contributed to open the theory to criticism around the idea of hierarchizing the human needs in a defined classification.

- The Two-Factor Theory of job satisfaction from Herzberg (1959):

The two-factor theory from Herzberg (also known as Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory or Dual-Factor theory) simply states that, in the workplace, there are two sets of elements, one being responsible for the job satisfaction whereas the other one causes job dissatisfaction.

According to Herzberg, the hygiene factors (also known as extrinsic factors) such as salary/wages, work conditions, company policy, relationship with peers and boss can lead to dissatisfaction if absent or insufficient but are not a condition to create motivation. On the other hand, the motivators also called intrinsic factors, that include among others recognition, growth, responsibilities, achievement, lead to positive job satisfaction and motivation.

- Vroom’s expectancy theory (1964):

In simple terms, Vroom suggests in his expectancy theory that the motivation to act on something is based on the analysis of the 3 following parameters:

- the estimation of the probability of success (or performance level) for a given effort

- the probability of being rewarded for the provided effort

- the perceived value of realizing the objective for the individual.

- The Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) from Deci (1975):

The result of a large number of psychology researches in various countries has clearly shown that motivation cannot be reduced to extrinsic reinforcement, ie to the act of reinforcing behaviors by rewards / punishment (the famous carrots and sticks). More importantly, it has also revealed that what is called intrinsic motivation leads to a superior job satisfaction and performance.

The Cognitive Evaluation Theory from Deci highlights that intrinsic motivation results from two fundamental human needs: the need to define one’s activities autonomously, ie the self-determination of activities, and the need to feel competent and to increase one’s competencies while executing those activities (note here that Deci refers to a subjectively perceived competency).

As mentioned, the intrinsic motivation generates a much higher job satisfaction but it can be hindered by material rewards, by punishment threat or also when people feel exaggeratedly monitored, controlled or evaluated. Under the influence of those external factors, the activities are no longer performed for the pleasure that they deliver but for the advantages that are expected in return (or to avoid punishment). As a matter of fact, Deci and Ryan (2000) explain that those hindering factors contribute to a feeling of imposed behavior, reducing thus the feeling of self-determination.

As a conclusion to the psychology of motivation, the journalist Daniel Pink summarizes in his 2009 book “Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us” what motivation is about by the following sentence: “Carrots & Sticks are so last Century. Drive says for 21st century work, we need to upgrade to autonomy, mastery and purpose.”

More concretely, how to work on staff “motivation” on the field?

Through empiric observations of your staff, no doubt that you will easily reach the conclusion that inner driving forces differ from one individual to the other. Everybody is unique: different staff, different motivations. Besides, one’s own motivation may also vary based on the environment, experiences, personal growth and other modification of the context. What one needs today may not be what one’s need tomorrow; what one is motivated for today may not be what creates excitement and pleasure tomorrow…

Obviously, your best staff will be the self-motivated ones where there is a perfect alignment between their personal motivations and your company’s objectives. In other words, in this ideal case, the individual purpose and related motivation of your employee matches and serves spontaneously the company’s objectives and in return the self-determined work activities naturally deliver entire satisfaction to the staff, allowing them to increase their competencies and fulfilling their personal objectives. As a manager, you then have the important duty to cherish this precious aligned self-motivated staff and to find ways not to get them demotivated… In reality though, rare are the teams composed exclusively by aligned self-motivated staff; you then have the difficult responsibility to bring everyone at the highest level of motivation possible in order to ensure superior performance.

It becomes then clear that your first step, as a manager, is to spend time with each one of your direct reports, individually, in order to understand what motivates them and equally important what frustrates them in their current assignment. By starting with simple questions and smoothly deepening the answers, try to capture what makes your staff excited, passionate about their jobs, identify which activities generate the biggest pleasure for them. Also be cautious enough to differentiate the components at the origin of an absolute motivation (what makes that your staff will look for another job tomorrow or not) from the ones related to a relative, punctual motivation (what makes a given task or a certain activity attracting and motivating or not in an overall context). You may re-assess those motivation parameters on a regular basis to help you to sort out the absolute ones from the punctual context-specific ones.

As a second step (and more especially in case you could not get a clear understanding of your staff inner driving forces following your discussion), simply observe the behavior of your team: how does a given employee react on his various assignments? Which topics seem to be generating the most excitement for him? Under which circumstances does he take spontaneously the lead or the responsibility? What type of discussions within the team trigger conflicts or even aggressive reactions? Which comments do you get when running the objective assessment interview? What are the questions from your staff when you communicate a policy change (introduction of flexible work, contract adjustment…) or when you share the details of bonuses or salary increase?

Thanks to those 2 steps, you should soon be able to figure out the combination of parameters (and their respective weight) composing the motivation of your staff. It becomes then easier, in a third step, to define the best approaches to decrease a growing job dissatisfaction or to increase your staff motivation. For example, depending on what you have identified as key motivation parameters, you can think of offering new growth opportunities, extended responsibilities, specific financial rewards, coaching session, training… It is equally important to detect factors being a source of frustration or disengagement at work such as difficult interaction with colleagues, excessive pressure, unchallenging tasks, and to act on those hurdles, removing them from the way of your staff commitment and success.

Be creative! Motivating each one of your single staff and/or keeping them motivated is definitely worth your time investment and effort. It will contribute to generate a positive dynamic work environment that will ultimately translate into a greater team outcome and performance.

Practice:

- exercise – motivation self-assessment: Answer spontaneously the following questions. Once finished, review your answers; what does it tell you about your values and interests? What can you deduct regarding your motivation?

- Which assignment in my current job gives me the most satisfaction?

- In the past 6 months, which initiatives have I spontaneously taken at work, without being solicited by my hierarchy?

- When interacting with peers or when discussing about my job, which topics do I really get excited about / on what type of topics do I really become defensive or look personally attacked?

- What type of work / activities should I avoid?

- If I had one factor that would trigger me changing my job from one day to the other, which one would that be?

- exercise – motivation questionnaire: Rank from 1 to 5 the below elements based on the importance you attribute them (1 = not important at all, 5 = very important)

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – salary, wages and other benefits

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – work/life balance

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – recognition

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – autonomy

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – status and title

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – opportunities for growth and learning, challenges

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – power, responsibilities and decision-making

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – competence and expertise

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – culture, affiliation and relationship with colleagues

- [1]…[2]…[3]…[4]…[5] – work environment

- exercise – assessing your staff motivation: When initiating a discussion with your staff to identify its motivation, try to get answers to the below questions.

- What makes you tick and what makes you frustrated in your current role and work environment?

- What gives you the most pleasure in your today’s job?

- Which personal short-term and long-term work objectives would you set (or have you set) for yourself?

- What type of support would you need to improve your performance further?

- Which activities or tasks that you are not involved with today would you like to be part of?

So What?

Because motivation appears as a key parameter to performance, many psychology researches have tried to capture what defines employee’s motivation in the workplace. The most recent studies shows that an employee commitment and performance is much more solid when the motivation is based on intrinsic parameters such as the ability to autonomously define its own activities and the perception of competency; this is especially true when those factors are coupled with an alignment of the company’s missions with the individual objectives, bringing thus a clear overall purpose for the employee. In parallel, it has also been demonstrated that extrinsic motivation answering to a logic of reward/punishment delivers much lower result and commitment. It even impacts negatively the intrinsically motivated staff under certain conditions. External rewards though can help answering a growing job dissatisfaction, which is to be clearly differentiated from generating motivation (decreasing a growing job dissatisfaction is not similar to increasing motivation).

Assessing what keeps your staff coming at work every day and what will make them driving the extra-mile for the company and themselves should consequently be one of the focus of every manager. Before defining any motivation strategy for your team members, it is strongly recommended to engage in individual discovery discussions and to simply observe behaviors and reactions of your staff under various situations and contexts; this will help you in identifying what generates motivation or dissatisfaction for them. It becomes then easier to act on those factors and create a high-motivation environment leading to long-term commitment and performance.

Setting objectives: better than SMART is SMARTER.

Posted by encognize G.K. in Know your business on February 13, 2012

“I often say that when you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it.”

– William Thomson, also known as Lord Kelvin, Scottish physicist (1824-1907)

Abstract:

In order to execute efficiently on your company strategy while supporting the personal development of your staff, it is your duty as manager to set and share adequate team and individual goals. A commonly used management method recommends defining SMARTER criteria for your goals: the objectives must be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound as well as Evaluated on a regular basis and Recognized/Rewarded when achieved or Revisited when not.

Download a one-page executive summary here (PDF or JPEG format): Team and Individual Goals: Be SMARTER

Concept:

Setting team and individual objectives is a key process that allows your team to focus on a long-term unified direction by defining clear targets to reach and by measuring the progress towards those targets. It also helps to increase your staff engagement and their job satisfaction by offering them some personal rewarding challenges supporting their personal development. Obviously the goals that you set directly derive from your company strategy, match its values and take into account the missions and maturity of your team and each of its members.

The most classical management method for setting objectives proposes to follow “SMARTER” criteria. Your objectives must be:

- Specific: the goal must be explicitly defined, without any ambiguity. It cannot be subject to individual interpretation but must explain specifically what has to be achieved and the type of outcome expected.

- Measurable: the completion criteria and related quantitative or qualitative measurement method must be clearly described. In other words, you must be able to answer the question: “How will I know that the objective is attained and which evidences are required to confirm it?”

- Attainable: this criterion emphasizes the importance of setting an objectives that is challenging for your team but nonetheless reachable against the existing constraints. It also requests you to assess whether the objective is realistic taking into account the other objectives that you have already set for the same employee. If the target is out of reach, your objective will become meaningless. This criteria also poses the question of the resource, authority and means needed to accomplish the objective: confirm how the goal can be reached (specific skills to be acquired, training available, human or financial resources, level of authority…). An objective cannot be reached “by all means” but through method and means aligned with your company ethic and values.

- Relevant: the goal must be tied to your organization priorities and to the employee maturity in his role. Goals that align to your company strategy, the team mission and the employee development and that do not conflict with other objectives are relevant. It also requires to check whether the timing for the objective is appropriate.

- Time-bound: this criterion stresses the importance to specify an appropriate time frame for your goal: when is it supposed to start and to end? What are the steps and critical milestones to accomplish it? What are the intermediate outcomes expected and by when? Answering those questions contributes to define a sense of priority for your staff and helps them to organize their tasks around their various objectives.

- Evaluated: as a manager, it is your responsibility to set challenging goals for you team but also to support your staff in reaching their targets by assessing the progress on a regular basis and by providing some recommendations or coaching session to overcome eventual obstacles. Define some specific checkpoints (at a predefined frequency or at critical milestones) and the related expected deliverables. Do not wait for the objective to reach its time-limit to deliver your feedbacks: this is counter-productive because it does not support the development of your collaborator and may even create frustration if the target is missed. The final evaluation result of the objective completion should not come as a surprise to your employee but should be the reflect of the intermediate reviews plus the evaluation of the last mile and its final output.

- Recognized/Rewarded or Revisited: when reaching the end of the time frame defined for the goal execution, run the final evaluation to assess the success or failure in achieving the objectives. Ask your employee for the lessons learned while executing the objective. What would they do differently next time? Why? What could they manage easily? What were the main obstacles? How have they been able to overcome them? What have they learned? If the objective is reached, explain the type of reward that the employee can expect (impact of the evaluation on possible promotion or mobility, extended responsibilities and autonomy on similar activities at the next opportunity, monetary compensation…) and in any case recognize the accomplishment. It is important to praise the employee for his performance, especially when outstanding. On the other hand, if the outcomes are below expectation, it is crucial to run a full review with your employee to understand what went wrong and why. Ask penetrating questions to get to the essence of the issue and share ideas on what could have been done differently. This discussion allows you to revisit the objective in order to draw the appropriate conclusions and should become the basis for defining new goals that will help your employee to improve his weak areas.

What will make the success of your team and its members in achieving their goals is their capacity to own their objectives and focus on their execution regardless of the numerous distractions from their daily activities. From experience, in order to increase the sense of ownership, I recommend here to engage your team further by:

- having your team member propose their self-defined objectives; review if they are compatible with the overall organization missions and priorities as well as relevant for the employee development within the company and include them if this is the case,

- reviewing and agreeing together with your staff on the SMART criteria for the objectives you assign them; involve them especially on the means, resources and time frame definition,

- making sure to explain how those objectives will support their personal development, the team mission and the overall company strategy,

- asking your staff to print out their objectives once set and to keep them visible at any time in their work environment.

At the end of the goal setting exercise, each employee should be able to express clearly the following:

“My company objective is to XXX ; our team will support this goal by XXX ; my personal contribution to this mission is to XXX .”

Practice:

- exercise 1: Are the following objectives SMART? If the answer is “no”, what is missing and how can you correct them to make them SMART?

- To a Developer: Reduce the number of open critical bugs for Product P by 30% by the end of Q2

- To a Sales executive: Increase number of deals signed by 60%

- To a Service Desk engineer: Create a knowledge database that will list all critical incidents and their respective solutions and that will be accessible to all Service Desk members by the end of the year.

- To a Client Relationship Manager: attend training for Product P

- exercise 2: Take one of your current objectives; is it SMART? If the answer is “no”, what is missing?

- exercise 3: Review the objectives that you have set for your team members. Are they SMARTER? How can you adjust them if this is not the case?

So What?

In most of the cases, managers with teams set for success go really instrumental when defining and assessing the objectives for their teams and respective members. They define goals that not only reflect and support the organization strategy and mission but also that inspire and motivate their collaborators by making sure that those goals are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-bound. Then they spend time providing regular feedbacks and intermediate Evaluation and make sure that the employee is Reocgnized/Rewarded when the target is achieved or that the objective is Revisited through adequate review when it is missed.

Answer to exercise 1: 1. yes – 2. no – 3. yes – 4. no

Last Revision: 2015 March 24

When 20 means 80… Pareto principle to support managers in tactical decisions.

Posted by encognize G.K. in Know your business on February 1, 2012

“The good-to-great companies did not focus principally on what to do to become great; they focused equally on what NOT to do and what to stop doing.”

– Jim Collins, US business consultant and author (born 1958) in “Good to Great”

Abstract:

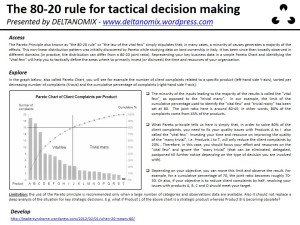

The Pareto Principle also known as “the 80-20 rule” or “the law of the vital few” simply stipulates that, in many cases, a minority of causes generates a majority of the effects. Representing your key business data in a simple Pareto Chart and identifying the “vital few” will help you to define the areas where to primarily focus (or not) the time and resources of your organization.

Download a one-page executive summary here (PDF or JPEG format): The 80-20 Rule (Pareto Principle) for tactical decision making

Concept:

Vilfredo Pareto (1848 – 1923) was an Italian civil engineer, economist and sociologist who had great interest in studying various social distributions such as income and land ownership. After collecting and compiling a large number of data, he has noticed that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. As Pareto studied other domains, he observed that the same non-linear distribution pattern was persistently reproduced.

This pattern, where a minority of the inputs is responsible of the majority of the outputs, was later called the “Pareto Principle” or “80-20 rule” and has been since then broadly observed in different domains. Note that, in reality, the distribution can obviously be different from a 80-20 joint ratio (As a matter of fact, following Pareto’s initial discovery and conclusion, those figures are commonly used to explain the principle itself).

The minority of the inputs leading to the majority of the results is called the “vital few”, as opposed to the “trivial many”.

In the graph below, also called Pareto Chart, you will see for example the number of client complaints related to a specific product, sorted per decreasing number of complaints, (left-hand side Y-axis) and the cumulative percentage of complaints per product (right-hand side Y-axis). What Pareto principle tells us here is simply that, in order to solve 80% of the client complaints, you need to fix your quality issues with Products A to I also called the “vital few”. Investing your time and resource on improving the quality of the “many trivial”, ie Products J to T, will only reduce the client complaints by 20%…

It is then clear that Pareto principle becomes a simple but nonetheless powerful tool to support your investment decisions (resources, money, time, energy…): focus on the “vital few” and ignore the “many trivial” (that can be eliminated, delegated, postponed till further notice depending on the type of decision you are involved with).

Note though, that it is recommended to use this principle only when a large number of categories and observations data are available. Besides, interpreting the data under a Pareto prism must not prevent you from running a deeper analysis of the situation. What if Product L of the above chart is a strategic product for your company in the coming years whereas Product B is becoming obsolete? Focusing on improving the quality of the “vital few” products will for sure help increasing your client satisfaction on the short-term but what about your mid/long-term investment strategy? Shouldn’t you start now with resources working on enhancing Product L as well?

Practice:

- case 1 – in a Service Desk management role: how does the Pareto distribution of the incidents raised per customer look like? On which “vital few” customers will you focus first to reduce drastically the number of complaints?

- case 2 – in a Sales or Business management function: draw the Pareto Chart of your organization profit generated per customer. Who are the customers that you will NOT put under a dedicated relationship management program aimed at reinforcing retention in a first stage?

- case 3 – in a Quality Assurance management position: What are the functionalities of your software used 80% of the time by your users? What can you deduct for your QA resources allocation and test automation initiative?

So What?

Defining the relevant long-term investment strategy for your organization usually requires an exhaustive, time-consuming analysis and interpretation of a large set of data. Nevertheless, for a short-term tactical allocation of your resources, interpreting your key data under the Pareto principle turns to be an efficient method to set quickly your priorities: identify and focus your effort on the “vital few” items/tasks that will give the majority of the results and disregard the “many trivial” others!

Last Revision: 2015 March 28

Deep diving around Bjørnøya: the virtue of questioning

Posted by encognize G.K. in Know your business, Know your team on January 25, 2012

“The important thing is not to stop questioning. Curiosity has its own reason for existing.”

– Albert Einstein, US (German-born) physicist (1879 – 1955)

Abstract:

When discussing with your teams or customers, be it unintentionally, due to time constraints, or to hide some precious insights, one is very often given with partial information only. It is therefore recommended to spend time exploring “the below part of the iceberg” using a specific questioning method in order to improve the relevancy of your critical decision calls.

Download a one-page executive summary here (PDF or JPEG format): Uncovering the truth: think iceberg

Concept:

In the same way that you would not invest your personal saving in stock options without knowing and understanding the performance of the underlying instruments, you do not want to make decisions or commit on critical matters without getting the full picture.

Nevertheless many reasons may prevent your interlocutor from shedding the Hollywood projector light on the reality: time constraint, fear of the management reaction (complaint from an employee), desire to hide information (prospect negotiating a contract), lack of self-awareness (employee in burn-out)…

Grasping the lower level realities of your interlocutor requires times, tact and method. From experience, the best way for exploring the untold is to ask questions following the below criteria:

- ask one question at a time in order not to bring confusion to your interlocutor,

- ask open-ended questions (how/what/why/in what way/to what extend/tell me more about/elaborate…),

- ask probing questions (questions that require detailed answers),

- ask non-leading questions (questions must not direct your interlocutor to specific answers),

- ask questions that focus around the matter of concern and that your interlocutor will connect to (initial topic, answer to the previous question),

- ask unbiased questions (questions that are not based on your assumptions).

The more you ask, the deeper you may have to dive and explore… Take your time.

Obviously, this uncovering exercise will request you to reach initially a certain level of confidence and trust with your interlocutor. This may not come with the first interview, meeting or discussion; therefore try to identify when the time has come to go under-water. You may also think of specific arrangement and behavior to help you break the ice before your deep diving:

- book a time-slot long enough to discuss comfortably without being in a rush (respect though the time constraints of your interlocutor),

- ease the sharing by selecting the appropriate environment: for example, round or oval tables usually support sharing ideas (contrary to squared tables that emphasize opposition or hierarchical position),

- remove any attention-catcher from the environment in order to stay focus while discussing (turn-off your screen, phone, shut the door of your office…); this will strengthen your listening ability and also show greater respect to your interlocutor,

- comfort your interlocutor on the confidentiality of your talk if necessary (and respect it!),

- think of being off-site, around a coffee or at lunch, or at least find a neutral place to break the regular context that may model the behavior and answers of your interlocutor,

- listen more than talk and give enough time your interlocutor to answer,

- acknowledge verbally what has been said before moving to the next question,

- introduce the difficult questions smoothly,

- keep eye-contact in case of face-to-face meeting.

A complementary approach is also to think under which conditions you would be more inclined to share your “secrets” or run uncovered with somebody. What works for you may work for others…

Of course, thank your interlocutor for his time and honesty at the end of the discussion.

Practice:

- scenario 1 – a recruitment interview: you need to evaluate a candidate on his team working competency. The candidate already told you in generic terms that, in his previous jobs, he has always been considered as an efficient team worker by his superiors (top part of the iceberg). Imagine questions that will allow you to uncover the candidate’s true abilities to work as a team and to foster team spirit.

Examples:

“Tell me about a time when you disagreed with other team members. How did you resolve the issue?”

“Share with me some initiatives you had taken as a team member to improve the overall team performance.”

And finally you have discovered that not only the candidate was unable to propose and participate to team development activities but that he was also unable to cope constructively with conflict situations within a team…

- scenario 2 – a staff complaint: based on the analysis of your resource planning, you have just adjusted your organization by requesting your team to support a new product suite very similar to the existing one from a technology standpoint. This new task comes on top of their current support tasks but the data supporting this decision are accurate, reliable and shows the necessary bandwidth within the team. Nevertheless, one of your staffs who recently looked overwhelmed by those changes has requested for a one-on-one discussion and tells you: “This new organization cannot work for the team! I will never be able to support this new product when I am already overloaded with a long list of issues to close!” (top part of the iceberg). Which questions would you ask your employee to understand and answer the real concern?

Examples:

“In what way do you think that our team will not be able to cope with this new assignment?”

“What would you suggest to better balance your workload between solving the current issues and the support activities around the new product?”

After a few round of questions, you have understood that your employee had simply needed a bit of support in reviewing the priorities of his issues regardless of the product suite. You have also discovered that his main concern was to take over the support of a product that he had been told to be very complex where in fact no extra technical knowledge was required…

- scenario 3 – a prospect demand: you are negotiating an important contract with a new prospect in a country where you do not have a local presence. Suddenly, the prospect turns to you and says: “You know, for such a complex solution, we will need a local support team. You will provide us with local support, right?” (top part of the iceberg). Think of questions that will allow you to move from this demand to the real underlying need in order to enable an effective negotiation.

Examples:

“Would you mind elaborating on your “support” definition?”

“In which areas and to what extend do you see a local presence being more efficient than any other type of support?”

Drilling down on the initial demand, you have finally uncovered the need for a technical service desk that would match the local regulation in terms of support hours and that could speak the local language. You have been able to easily negotiate that your 24×7 multi-lingual centralized support center would perfectly answer this need, as it is already the case for other specific countries.

So What?

Poor, wrong or incomplete information almost systematically results in inadequate decisions and answers, regardless of the situation. As a manager, it is your responsibility to make wise choice for your organization and employees in any circumstances. An appropriate questioning method will therefore support your decision-making process by allowing you to drill down and uncover the essence of a concern or of a need.

Last Revision: 2015 March 24

About Leader Syndrome

Posted by encognize G.K. in Uncategorized on December 31, 2011

In a fast-pace, time-pressured, high stress environment, today’s managers are given only few opportunities to step back and think about what made them successful or what could contribute further to the path of excellence as leaders. This statement is even truer for those who have just been promoted managers and who are coping with their new responsibilities with often minimal preparation only.

This blog, proposed by DELTANOMIX, is not about being right or wrong. This blog is not about being scientifically exhaustive about management and leadership. This blog is about sharing experiences, lessons learned and other useful concepts that have helped the author in building and improving his management and leadership skills overtime in order to serve and grow for-profit organizations in a sustainable manner.

Because every individual, every team, every business has got its own dynamic, growing teams in a for-profit structure can be seen as the fine art of positioning meaningfully leaders, teams and business or activities by exploring and understanding individually as well as holistically those three components, their related contexts and interactions. These blog’s posts will therefore fall under one or several of the 3 categories below:

- the “know thyself” category groups ideas on how to support and improve your performance as an individual with management responsibilities,

- the “know your team” category obviously gathers concepts and experiences on how to grow your team by learning how to work and interact efficiently with them in order to achieve the company’s missions,

- the “know your business” category consists in providing posts that will help you to grasp your overall environment. You have to understand “business” in its broader meaning, covering various areas ranging from industry knowledge, client approach but also ideas and definitions around the role of manager itself.

DELTANOMIX hopes that those Leader Syndrome Blog Posts will be thought-provoking enough to enrich your day-to-day experience in your role of today’s and tomorrow’s global leader who can shape a brighter future!

To learn more, visit us at www.deltanomix.wordpress.com or contact us at: deltanomix@gmail.com.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use.